The COVID-19 pandemic has gripped the world and shaken the healthcare system. It is important that the childhood obesity pandemic is not cast into the shadows as a result. The Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre in the UK reported that 31.4% of all critically ill patients admitted with COVID-19 had a BMI >30kg/m2 and that high BMI was strongly associated with COVID-19 related deaths.(1- see references below) This highlights the importance of obesity prevention more than ever and the need for healthy lifestyles to protect against adverse health outcomes.

Evidence suggests that the pandemic may already be influencing children’s lifestyles and increasing their risk of having overweight or obesity. A recent study looking into the impact of COVID-19 confinement at home in a small cohort of Italian children found evidence of increased consumption of high calorie and sugar foods, and decreased time spent in sport activities.2

From as early as the 1990s, childhood obesity has been a growing concern. The World Health Organization estimated the number of children under five with obesity increased from 32 million to 41 million between 1990 to 2016.3

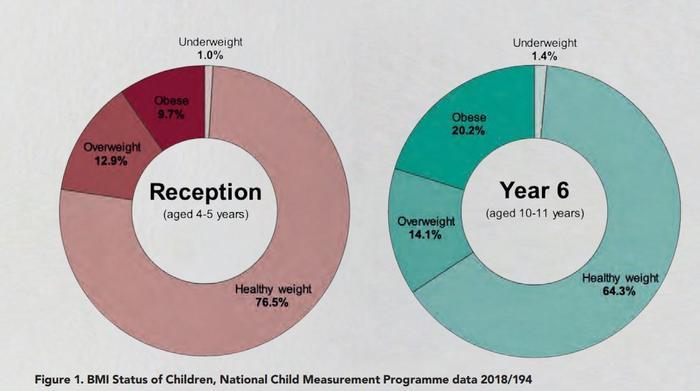

In the UK, 9.7 % and 20.2% of children aged four-to-five years and 10-11 years respectively were classed as obese or severely obese in 2018/19 based on data from the National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP). Compared to 2009/10 NCMP data, this represents an overall increasing trend.4

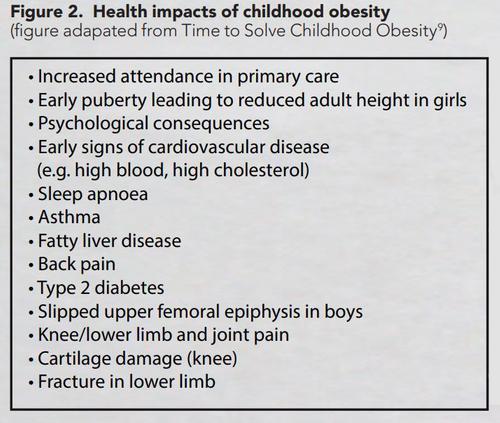

Health status in early life sets the trajectory into adult life, and maintenance of healthy body weight is important to protect against comorbidities associated with obesity such as hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, type 2 diabetes, musculoskeletal pain and poor mental health (see figure 2).5 It has been suggested that children who are obese are five times more likely to become obese as an adult.6 Consequently, obesity places a considerable economic cost on healthcare systems therefore efforts to reduce this preventable burden are essential.7

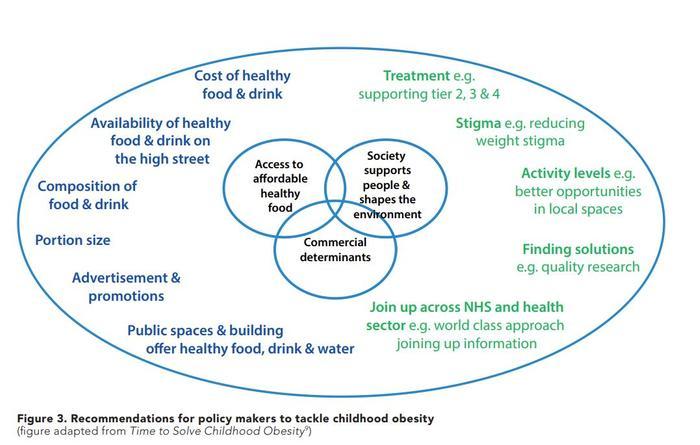

Obesity cannot be simply considered as an energy imbalance caused by excessive calorie intake, reduced physical activity and increased sedentary lifestyle, but is largely implicated by a multitude of factors. These include psychological mediators (e.g. emotions, selfregulation, perceived environment), socio-economic status (e.g. income, deprivation) and local/national settings (e.g. advertising, access to food retailers/service outlets, food labelling, cultural setting and policy).8 Poor health literacy (e.g. education on health risks) can also be considered as a contributing factor. Together, these can create and favour ‘obesogenic’ behaviours and an environment which promotes excessive weight gain.

There is a well-recognised gap between health and social inequalities. Data from the recent NCMP report 2018/19 demonstrated that childhood obesity is strongly correlated with socioeconomic status, as prevalence of childhood obesity was twice as high in those living in the most deprived areas compared to the least.4 Whilst a whole-systems approach is important to address features of the obesogenic environment and encourage behaviour change at a societal level, childhood obesity must also be tackled at the individual level without exacerbating the gap between health and social inequalities. These approaches should help children and families navigate through complex obesogenic behaviours and environments to modify and improve health.

Government strategy in the UK

In the UK, the government set an ambitious target to halve childhood obesity by 2030, yet rates are showing an overall increasing trend.4

Several government strategies have been launched to tackle obesity, including Healthy Weight, Healthy Lives in 2008 and Call to Action on Obesity in 2011, but in 2017 the Childhood Obesity Plan was heralded to specifically tackle the growing problem in children. Critics of the plan outlined it did not go far enough to tackle the multifaceted issues surrounding obesity, particularly missing the importance of commissioning lifestyle weight management services, or considering the role of dietitians in obesity prevention and management.

An independent report, Time to Solve Childhood Obesity, by the former Chief Medical Officer was published in 2019 which outlined a set of proposals that went beyond the current government strategy, and highlighted the importance of commissioning Tier 2, 3 and 4 weight management services for children. More stringent recommendations on affordable healthy food were also outlined, as well as addressing the marketing of food and drinks high in fat, salt or sugar (see Figure 3 for a summary of recommendations).9

Earlier this year the Welsh government published their comprehensive 10-year plan, Healthy Weight, Healthy Wales, outlining a strategy echoing much of the independent report and shone the spotlight on dietetics by committing to implementing evidencebased, dietetic driven, lifestyle weight management programmes.

Leeds demonstrated a reduction in rates of obesity in children aged five from 9.4% in 2009 to 8.8% in 2016, and prominent results were seen amongst those living in the most deprived areas where rates dropped from 11.5% to 10.5%10. However, latest NCMP data (2018/19) reported that obesity in children aged five living in Leeds was 9.7%4 . It is difficult to identify the attributes to the period of success and how success could be sustained in Leeds without further research. It has been suggested that the reductions were the combined effect of access to affordable food, opportunities for physical activity and delivery of early prevention programme (tier 1), HENRY (health, exercise and nutrition for the really young).11 However, what’s vital is learning why impact was not sustained.

Evidence and guidelines for lifestyle weight management services for children in the UK

A large body of evidence exists to suggest that lifestyle weight management services require a multi-component framework, which is age-specific, personalised and culturally appropriate.12,13 NICE guidance published in 2013, Managing overweight and obesity amongst children and young people: lifestyle weight management services, explicitly outlines the core components of lifestyle weight management programmes (summarised in Table 1).14 Furthermore, those able to provide real-life experiences such as cooking sessions, supermarket trips or integrated physical activity have demonstrated greater success rates.15 However, the NHS is struggling to commission enough lifestyle weight management services at tier 2 (lifestyle intervention) and tier 3 (specialist intervention) level, for children.

Good examples of lifestyle weight management services in the UK include Planet Munch, formerly known as Trim Tots, which is one of the only programmes for pre-school children that complies with all NICE recommendations with RCT evidence to show it is effective in prevention and management of overweight. It is a 24-week based programme with a focus on learning as a family, through art and play. Results, published as an abstract in the Lancet, reported reductions in BMI Z-scores following intervention (mean difference (MD) in zBMI: -0.9, p=0.001) in children at high risk of obesity. Importantly, this effect was sustained two years later (MD in zBMI: -0.3, p=0.007)16.

LEAF (lifestyles, eating and activities for families) is an obesity treatment programme for severely obese children under six years, and prioritises families living in areas of high deprivation. The programme consists of several assessments and workshops, followed by a final review after three months. Evaluation of the programme found that BMI Z-scores (-0.4, p<0.001) and energy intake from drinks (z-score -4.77, p<00.1) reduced by the end of the programme.17

Overall, these programmes demonstrate successful outcomes and show that weight management services that target behaviours most strongly associated with obesity risk enable children and their families to implement healthy behaviours and lifestyle choices effectively.

New BDA Paediatric Specialist Group resources for childhood obesity management

Whilst much greater action is required at a national level including increased commissioning of lifestyle weight management services, the BDA Paediatric Specialist Group has worked with experienced dietitians in paediatric weight management to produce new resources. These new resources provide information to help achieve a healthy weight, available for children grouped according to age: under five, six-to-11 and 12-18 years. Furthermore, a healthy lifestyle guide is available to help families and caregivers to manage healthy lifestyle behaviours and choices. This range of new resources are available for purchase.

The BDA Paediatric Specialist Group has funded work to develop portion sizes for children aged four to 18 years, and a full report is undergoing preparation for submission to the Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics. However, the portion sizes are included in the latest edition of Clinical Paediatric Dietetics.18

Furthermore, the BDA Paediatric Specialist Group plans to develop the portion sizes into a practical guide that will enable easy translation into practice by dietitians managing children identified as overweight or obese.

Acknowledgements

Sarah Flack, Sarah Dunhoe, Sarah Wocka, Kerryn Lee Moolenschot, Kiran Atwal, Sarah Cawtherley, Julie Lanigan, Vanessa Shaw and Sue Meridth have all made significant contributions to the production and review of the new obesity resources on behalf of the BDA Paediatric Group and the work would not have been possible without their collective contributions.

References

- Williamson E, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran KJ, et al. OpenSAFELY: factors associated with COVID-19-related hospital death in the linked electronic health records of 17 million adult NHS patients. 2020:05.06.

- Pietrobelli A, Pecoraro, L., Ferruzzi, A., Heo, M., Faith, M., Zoller, T., Antoniazzi, F., Piacentini, G., Fearnbach, S. N., & Heymsfield, S. B. Effects of COVID-19 Lockdown on Lifestyle Behaviors in Children with Obesity Living in Verona, Italy: A Longitudinal Study Obesity (Silver Spring). 2020;30:10:1002.

- World Health Organization. Childhood overweight and obesity. 2016

- National Child Measurement Programme, England 2018/19 School Year. 2019.

- Franks PW, Hanson RL, Knowler WC, et al. Childhood obesity, other cardiovascular risk factors, and premature death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(6):485-93.

- Simmonds M, Llewellyn A, Owen CG, et al. Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2016;17(2):95-107.

- Frost GS, Lyons GF. Obesity impacts on general practice appointments. Obes Res. 2005;13(8):1442-9.

- Kremers SPJ, de Bruijn G-J, Visscher TLS, et al. Environmental influences on energy balancerelated behaviors: A dual-process view. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2006;3(1):9.

- An Independent Report by the Chief Medical Officer. Time to Solve Childhood Obesity 2019.

- Rudolf M, Perera R, Swanston D, et al. Observational analysis of disparities in obesity in children in the UK: Has Leeds bucked the trend? 2019;14(9):e12529.

- Thornton J. What’s behind reduced child obesity in Leeds? 2019;365:l2045.

- Ells LJ, Rees K, Brown T, et al. Interventions for treating children and adolescents with overweight and obesity: an overview of Cochrane reviews. International journal of obesity (2005). 2018;42(11):1823-33.

- Public Health England. A Guide to Delivering and Commissioning Tier 2 Weight Management Services for Children and their Families 2017.

- NICE. Weight management: lifestyle services for overweight or obese children and young people. 2013.

- Burchett HED, Sutcliffe K, Melendez-Torres GJ, et al. Lifestyle weight management programmes for children: A systematic review using Qualitative Comparative Analysis to identify critical pathways to effectiveness. Preventive Medicine. 2018;106:1-12.

- Lanigan J, Collins S, Birbara T, et al. The TrimTots programme for prevention and treatment of obesity in preschool children: evidence from two randomised controlled trials. The Lancet. 2013;382:S58.

- Lanigan J, Tee L, Brandreth R. Childhood Obesity. Medicine. 2019;47.

- Shaw V. Clincial Paediatric Dietetics 5th Edition: WileyBlackwell; 2020.